A new analysis from the $80 trillion-backed investor network FAIRR warns that most of the world’s largest protein producers are dangerously unprepared for the escalating threat of water scarcity, placing global food security and investor returns at risk.

The research briefing, “Water Insecurity in the Agri-Food Value Chain,” reveals that nearly two-thirds of the companies assessed in FAIRR’s Coller Protein Producer Index are failing to manage water-related risks effectively. The Index evaluates 60 of the world’s biggest publicly listed meat, dairy and aquaculture companies against sustainability themes linked to the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

The analysis also offers steps that business leaders can take to preserve water supplies — from mapping their full water footprint to setting basin-specific targets and standardizing how progress is measured. These actions, FAIRR says, are critical to safeguarding long-term water supplies as demand and stresses surge in the coming years.

“We are moving towards a future of water insecurity, particularly with the increase in intensity of droughts in different parts of the world,” Simi Thambi, climate and nature economist at FAIRR and co-author of the report, told Trellis in an interview. “It’s becoming a threat to business models, and yet it’s not explored that much.”

Source: FAIRR

Trace your water footprint beyond the factory gate

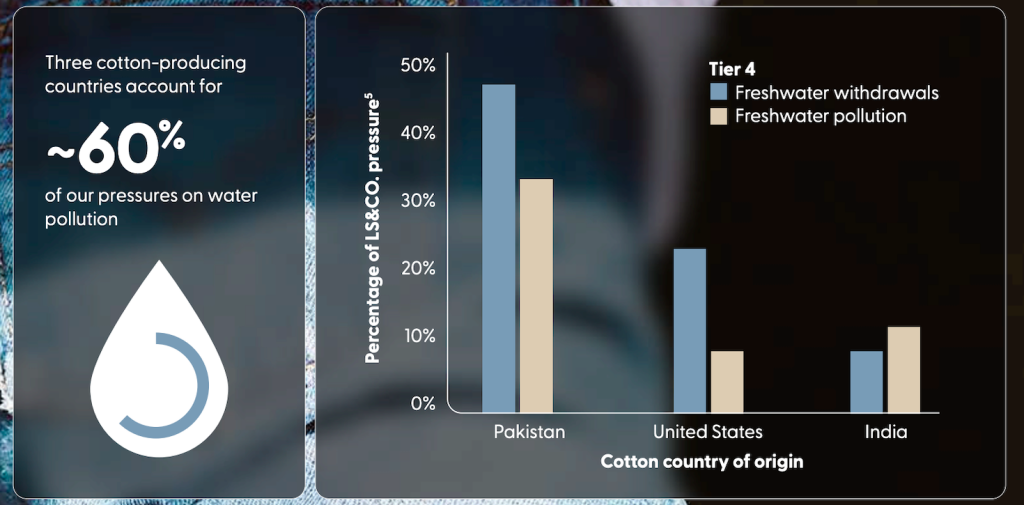

For many companies, the biggest water risks lie not in direct operations but in feed and supply chains. Yet FAIRR found that 84 percent of livestock firms fail to disclose where their feed crops come from — even when sourced from drought-prone regions such as northern China, India and the U.S. Midwest.

Only one, Texas-based egg and dairy producer Vital Farms, disclosed all feed sources from water-stressed areas.

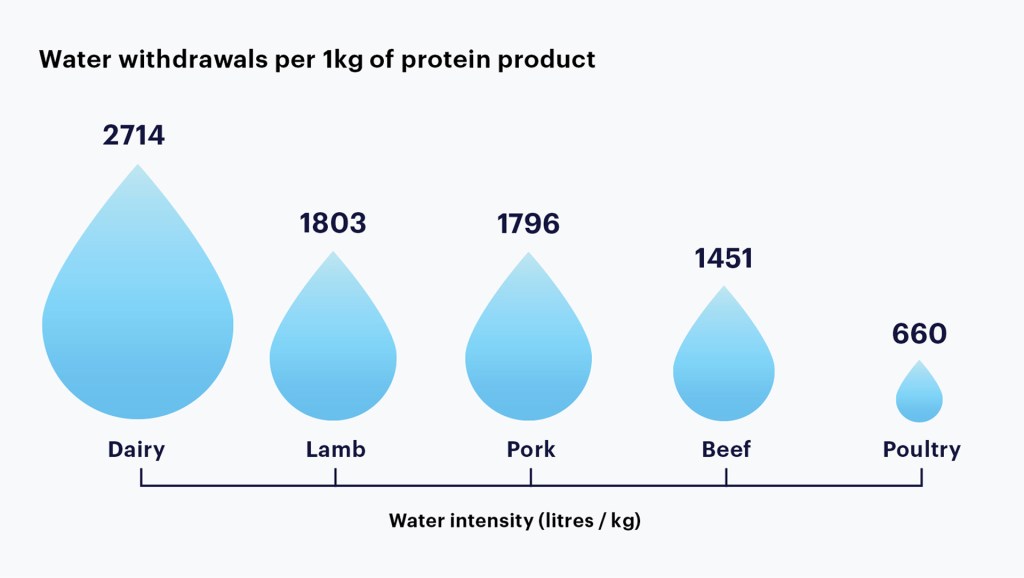

Others are likely under-reporting their exposure. Thailand’s Charoen Pokphand Foods, for instance, estimates its corn supply chain uses nearly 29,000 cubic meters of water per $1 million in sales — roughly 10 times higher than peers that count only direct operations. That difference highlights how much risk can remain hidden upstream.

“Supply chain disclosures of water usage and risk are very important because that’s where a lot of these water-intensive activities are concentrated,” Thambi said. “It’s not sufficient to disclose only direct operations because it doesn’t capture the full picture.”

Set basin-specific targets

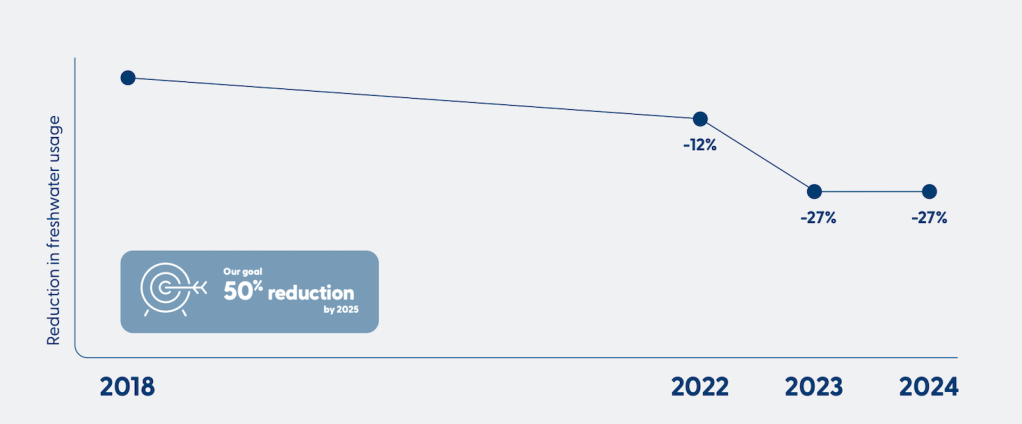

Only 10 companies in FAIRR’s 2024 Protein Producer Index have set targets to cut water withdrawals, and most focus narrowly on efficiency rather than absolute reductions.

By contrast, New Zealand dairy company Fonterra has committed to reducing withdrawals by 30 percent by 2030 at high-stress sites, while Charoen Pokphand has already achieved a 30-percent per-unit reduction domestically and is now expanding targets to overseas operations and suppliers.

The report also recommends tying these absolute reduction targets to executive pay. Such a move could be profitable for investors: BlackRock research cited in the report found that high-efficiency water users achieved better returns than peers.

Standardize metrics

Even when companies disclose water data, comparability remains poor. FAIRR urges firms to report water intensity per unit sales and link it to the source (groundwater, surface or rainfall) and stress level of each basin.

This would allow investors to benchmark risk and direct capital towards companies reducing withdrawals where it matters most.

The takeaway

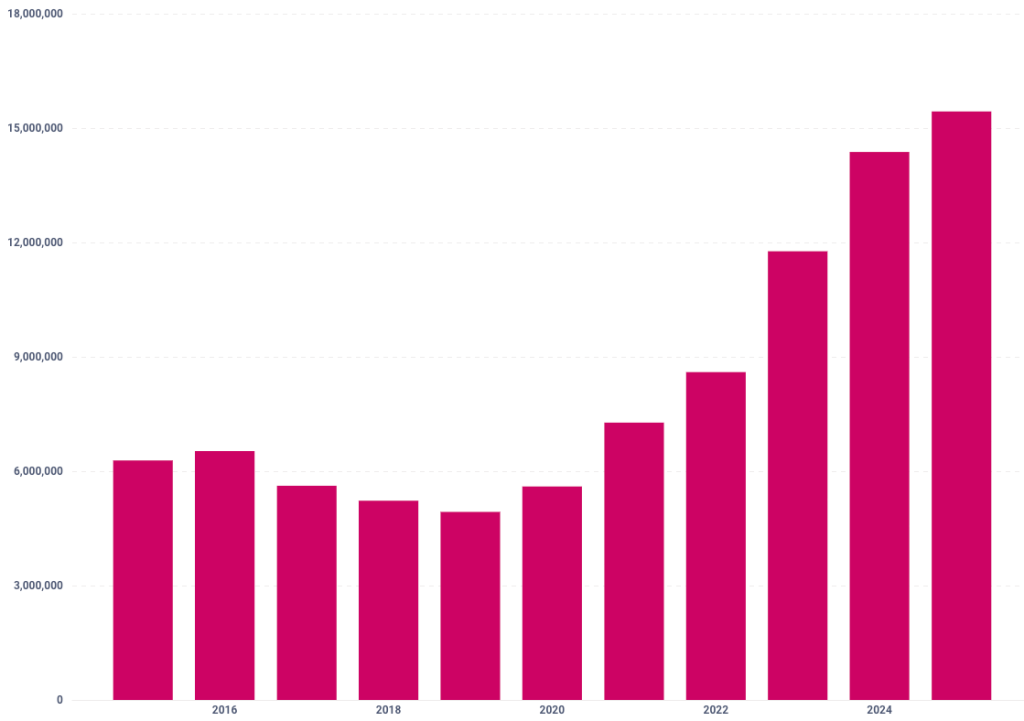

Global freshwater demand is projected to outstrip supply by 40 percent within five years. For the trillion-dollar livestock sector, the choice is clear: build water-resilient business models now, or face stranded assets and shrinking supply chains later.

“Just as big tech — and especially artificial intelligence — faces scrutiny over water use, a handful of highly dependent agri-food companies hold outsized influence in building water resilience,” FAIRR research manager and report co-author Henry Throp said in a statement. “It is critical that we understand the financial implications of water insecurity — and the value that can be generated in building resilience.”

The post Big meat producers must mitigate water risks. Here’s how appeared first on Trellis.