The opinions expressed here by Trellis expert contributors are their own, not those of Trellis.

Companies, especially big ones, rarely tell the whole story. Instead, they focus on what makes them look good. Their half-truths not only conceal their harmful impact on the climate, but also create the false impression that they’re helping solve the climate crisis. This illusion of progress makes them directly complicit with Big Oil, trade associations and other groups actively blocking real climate action.

Positive brand perception is vital for companies, so it’s entirely natural that they seek to burnish their reputations. That’s what marketing is for, after all. When it relates to climate action, however, there’s a larger social context at play and other actors seeking to delay progress. This means their marketing can have massive negative consequences for our ability to make progress on climate.

The corporate world is accelerating these climate half-truths under the current administration. Whether they’re failing to disclose working with fossil fuel companies or misleading the public about the scalability of climate tech, many companies contribute to a narrative that’s slowing climate progress at a time when we need it more than ever.

These claims downplay the scale of the climate crisis and of the rapid systemic changes needed, and create the illusion of progress when any meaningful benefit is years or decades away. By celebrating their contracts for direct air capture or nuclear energy, for example, some companies are promoting hypothetical future benefits without adequately acknowledging the present reality — glossing over the long and uncertain time frame until those technologies scale, not to mention the risks and high costs.

Overhyping future benefits

Just look at AI. A recent paper suggested AI climate solutions could reduce global emissions by 3.2 to 5.4 gigatons of CO2-equivalent by 2035, potentially outweighing the energy demands of AI data centers. These benefits are possible, yet highly uncertain in both timing and scale. What’s more, this estimate ignores the fact that tech companies are selling AI tools to oil and gas companies to expand fossil fuel production, causing direct damage happening now. This is a misleading picture, like a CFO touting revenue while ignoring expenses. It downplays the severity of the climate crisis and the need for immediate, large-scale action and omits any mention of massive current harms.

Microsoft is a prime example. Since its 2020 goal to become “carbon negative” by 2030, its reported emissions have grown 29 percent largely due to new AI data centers. Microsoft is relying on large-scale carbon capture, which is unproven at that scale, to bridge the action gap. Worse, the company actively markets AI technology for use by fossil fuel companies such as Chevron and Exxon, enabling massive emissions today that far outweigh the benefits of its operational actions.

But it’s not just the tech industry. Other sectors also promote their achievements and potential benefits, while downplaying or sidestepping harms. For example, many companies with stated climate goals (including Coca-Cola, Procter & Gamble, and Uber) remain members of trade associations, such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, that lobby against climate action. Others, such as law firms and companies operating in consulting, marketing, banking and insurance, tout their work with climate tech companies while also serving fossil fuel clients. By assisting the oil and gas industry with lawsuits, funding and public deception, these companies are complicit in “enabled emissions” generated at everyone’s expense.

Company silence hurts public perception and policy momentum

Many companies are now “greenhushing” — downplaying or staying silent on climate action despite internal progress — in response to environmental rollbacks. A Bloomberg analysis shows climate mentions on S&P 500 earnings calls have dropped 76 percent in three years, and some companies such as Pepsi and Salesforce are weakening their climate goals.

The issue is that corporate silence (or misleading optimism) distorts public perception, dampens support for regulation and slows political momentum. This mirrors past fossil fuel industry tactics, where massive marketing campaigns fueled climate denial and stalled policy change.

When companies do talk about climate change, they often highlight future technologies and voluntary efforts, seeming to suggest that markets alone can solve the crisis. This approach reinforces the misleading idea that strong regulation isn’t necessary, even though it’s both essential and often beneficial for business. For example, companies proudly promote their wind and solar purchases but fail to acknowledge the government policies — R&D funding, renewable mandates and tax credits — that made those investments possible.

Rather than focusing mainly on unproven innovations, we should prioritize deploying existing solutions — wind, solar, energy storage, EVs, heat pumps and grid upgrades — which can scale quickly with the right policies.

Yet most companies remain silent on supporting the very policies that would help them cut emissions, lower costs and ensure long-term viability. Consider the recent “Big Beautiful Bill,” which threatened many clean energy gains from the Inflation Reduction Act. Despite one analysis showing the act’s energy tax credits would create 13.7 million jobs and drive $1.9 trillion in economic growth, very few companies, including Amazon, Apple, Google and Walmart, publicly advocated to save these programs. In fact, some, including Uber, 3M and Cisco, even endorsed the House version of the bill.

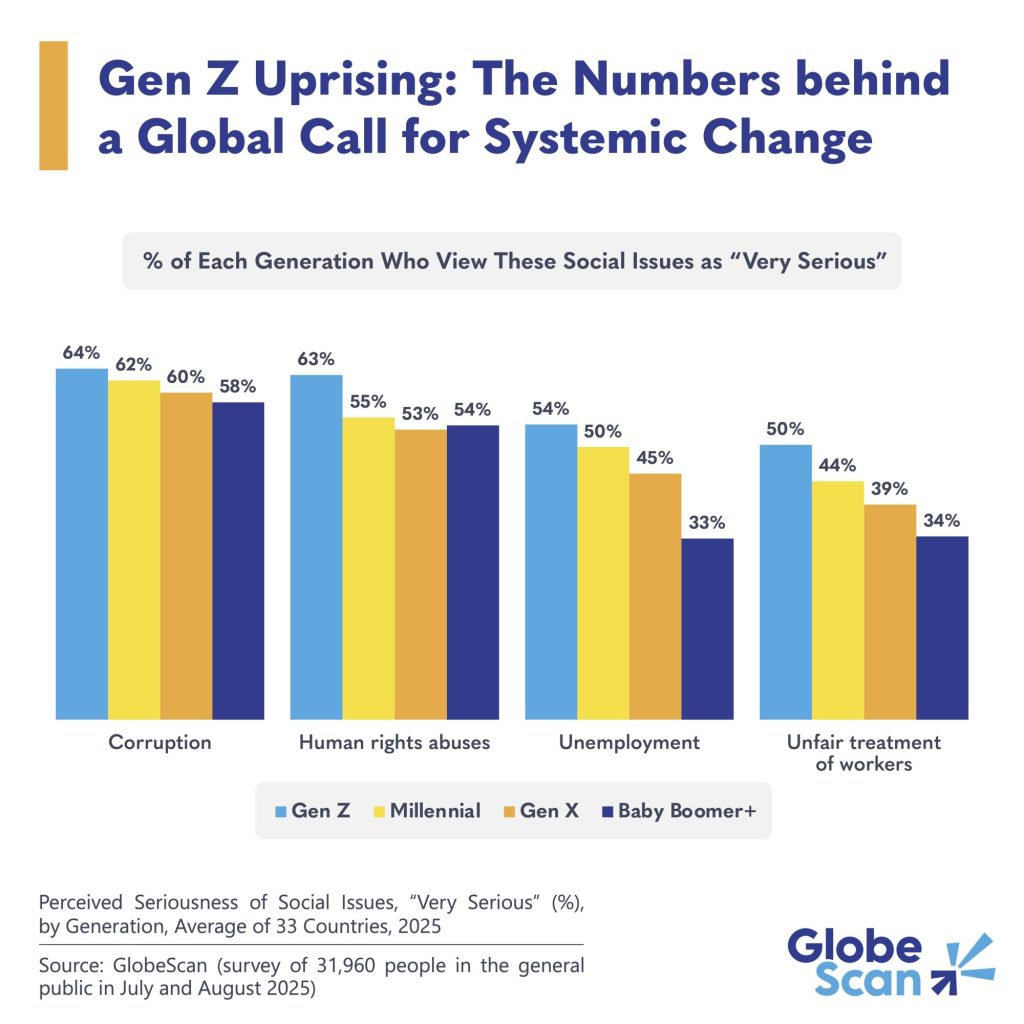

These companies may believe they’re protecting their business, but their actions contradict consumer desires. A September 2024 report found that three-fourths of Americans believe companies have a responsibility to limit their climate impact, and nine in 10 retail investors want companies to reduce emissions and prepare for climate impacts.

How to reverse corporate backslide

So, what should companies do differently? They need to be honest about the scale and systemic nature of the climate crisis. When discussing future technologies, they should clarify uncertainties in timeline, scale and cost, and emphasize that technologies don’t negate the need for rapidly scaling existing solutions. They need to be transparent about how their tech is being (or might be) used to harm the climate. They must also be honest and direct about the necessary government policies and regulations, and lobby hard for them.

Business has the power to move the needle and must step up to match the urgency of the crisis. Fortunately, tools already exist for business leaders, sustainability professionals and employees to steer companies toward meaningful action beyond half-truths and climate complicity:

- When you see companies telling half truths, help them tell the whole story. If it’s your own company, work with colleagues to paint a fuller picture. If it’s another company, join their conversation on social media to highlight the parts of the story they’re glossing over.

- Check out the Anti-Greenwash Guide for Agency Leaders published by Creatives for Climate and actively be on the lookout for ways to combat greenwashing and climate misinformation at work.

- Join the growing LEAD community of over 1,000 sustainability professionals who are committed to speaking up for meaningful climate policy advocacy at work. Recognize that advocacy is a long game, but will scale your impact as a CSO.

- Read and share ClimateVoice’s Employee Climate Action Checklist, which provides steps anyone can take to urge stronger corporate climate leadership and action at work.

Silence won’t lead to a brighter future. Moral courage, truth-telling, collaborative problem-solving and advocating for meaningful climate leadership will. We must hold companies and their leadership accountable to ensure they rise to the challenge, and quickly.

The post Half-truths and hidden lies: How large corporations undermine climate action appeared first on Trellis.