The opinions expressed here by Trellis expert contributors are their own, not those of Trellis.

For many companies thinking about climate change, carbon accounting is hot right now.

But most of the attention focused on accounting is really about improvements to existing carbon reporting frameworks. Both reporting and accounting have important roles to play in the push for decarbonization, but failing to understand the difference between the two will lead to compromised emissions management approaches that don’t stand a chance of arriving at their desired net-zero destinations.

We know this because reporting has been driving emissions information for the past three decades and yet greenhouse gases continue to rise and carbon markets continue to falter. The distinction may at first appear trivial but when it comes to climate, the difference between reporting and accounting frameworks marks the difference between hitting targets versus simply setting them.

Terminology 101

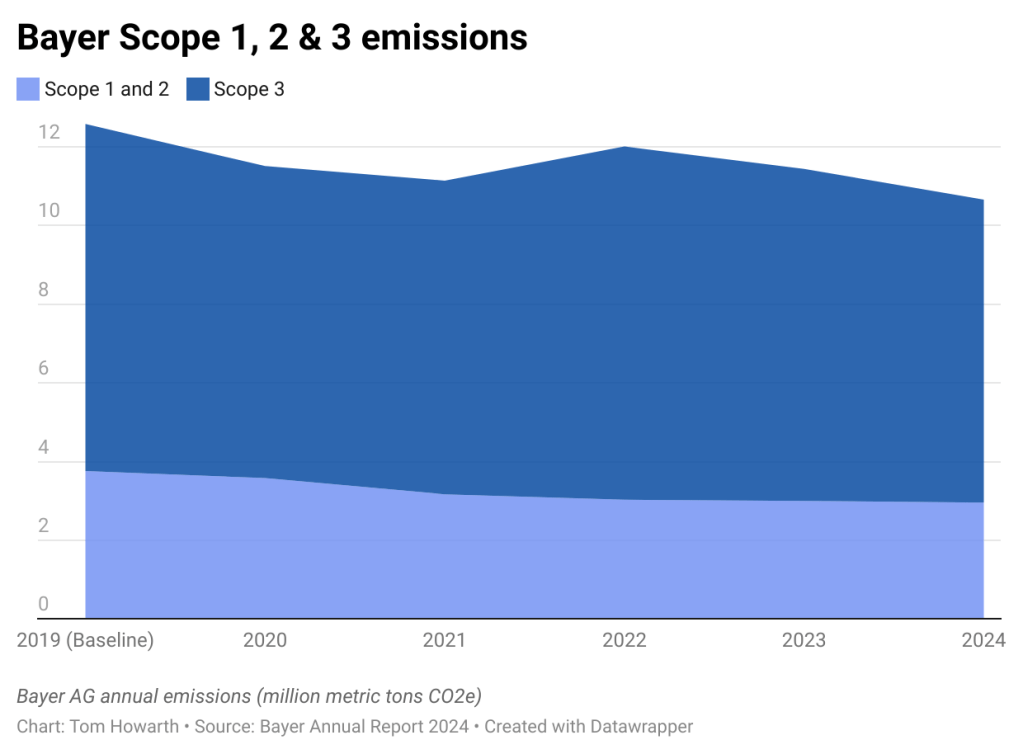

Climate-related reporting is a more general phenomenon than accounting. Reports can be based on qualitative disclosures, quantitative numbers, such as Scope 2 and Scope 3, that have no underlying basis in an accounting-system, or on accounting-based numbers. Greenhouse gas reporting frameworks count emissions according to a standardized set of rules to produce documentation that’s useful for three primary activities:

- Fulfilling a policy or voluntary requirement such as inventories and disclosure

- Enabling advocacy

- Documenting emissions alignment such as matching inventories to targets

Carbon accounting, on the other hand, requires every anthropogenic emission to be counted and fully allocated. The numbers must be accurate, verifiable, comparable, mutually exclusive across arm’s-length entities, collectively exhaustive and policy agnostic. In fact, only once policy-agnostic accounting has been put in place can emissions information-based laws and regulations be effective in steering high-emitting sectors through a decarbonization transition.

The primary purpose of a carbon accounting framework is to inform capital allocation decisions. It serves three critical functions:

- Unlocking investment for decarbonization through performance-based competition

- Facilitating demand for carbon removal through asset-liability matching

- Supporting accountability mechanisms, including governable net zero

Neither good nor bad

Reporting and accounting are neither inherently “bad” or “good,” but their application in specific contexts lead to different outcomes. In the case of greenhouse gases, reporting frameworks allow emissions (and reductions) to be counted multiple times or in some cases, not at all. Such indeterminate overcounting (or undercounting), along with the allowable use of estimates, averages and flexible boundaries, prevent competition for decarbonization while also obstructing the advancement of carbon removal that scientists deem necessary.

Reporting frameworks, which range from ISO standards to the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, allow emissions to exist on multiple “ledgers” at once and disappear by moving them beyond the reporting boundary. Companies can use reporting frameworks to produce “balance sheets” where emissions are labeled as “assets” and traded in the form of an avoidance. This is what makes the reporting/accounting paradigm so confusing; the terminology sounds the same but their effect on global emissions management is dramatically different.

In an accounting system, ledgers are used to record all anthropogenic emissions and can be added up to form a single record of global carbon stocks and flows. The E-ledgers Institute’s algorithm (of which I sit on the board) uses three types of journal entries. One to account for purchased emissions that transfer between a seller and a buyer; another for direct emissions transferred between the emitter and a geological carbon equity account; and a third to allocate emissions within a company to its products.

In the E-ledgers framework, emissions are recognized as E-liabilities and only removals can be recognized as E-assets. All emissions are counted only once so that at the geological scale assets = liabilities + equity.

Implications for carbon markets

Perhaps the most important distinction between reporting and accounting frameworks is their implications for carbon markets.

Carbon markets built on reporting systems lack integrity and enable a kind of shell game in the form of credit boundary design. That’s because reporting systems lead buyers and sellers to make claims based on reputational authority. Reputational authority is primarily derived from narrative arguments over additionality, permanence and leakage. The result: Carbon markets built on reporting frameworks are self-referential, highly gameable and prone to collapse.

The voluntary market was designed to be “better than nothing” in the absence of climate regulation. They offered a way to finance mitigation before governments acted, to reward early movers and to mobilize capital around a shared sense of urgency. To drive toward net zero, however, carbon markets can no longer depend on credibility narratives. They need something more stable, such as the laws of physics.

A carbon market built on an accounting system facilitates instruments with atmospheric authority — verifiable increases in carbon reserves that are tied to durable reduction of atmospheric emissions. Just as important, and more immediately, an accounting-based market facilitates investment in avoided emissions by capitalizing performance improvements in the form of lower E-liabilities. And through the principle of impairment, accounting provides guidance for recognizing and replacing a sudden loss in asset value thereby enabling the pursuit of permanence while opening markets for nature-based carbon removal.

Accountability: The ultimate imperative

Only an accounting system can provide a true and fair basis against which regulatory and voluntary mechanisms can durably hold emitters accountable. Feasible accountability mechanisms, such as carbon-border adjustments, product-intensity standards, supplier contracts and auditable voluntary net-zero claims, are ready for action.

Although sustainability professionals working today might not connect the dots to recent history, the U.S. stock market crash of 1929 and subsequent global depression was caused in part by a lack of accountability, as firms reported whatever profits, expenses, assets and liabilities they pleased. Then a group of committed academics, accountants, executives and philanthropists got together to create the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Financial accounting standards have endured because they enable decision-making and accountability. They allow investors to allocate capital based on accurate and comparable information rather than self-referential reputational claims.

To hit net zero targets, firms need GAAP for climate. Those defending carbon reporting frameworks are understandably afraid and skeptical. But steering with reporting frameworks won’t drive down emissions in the real economy. For that we need accounting. It’s a boring, centuries-old technology — but it’s the only one capable of filling the gap between ambition and action.

The post How to overhaul carbon accounting to save net zero appeared first on Trellis.