Their suitcases survive a car crash, a piano drop and a crowbar assault. Samsonite commercials from several years ago convey a longtime durability message that fits the company’s recent circularity push.

The luggage maker is increasingly making recycled and repairable materials central to its products and emissions goals.

“When we ask the luggage and bag consumer, durability is the top choice criteria, but repair and sustainable materials are other important considerations,” Samsonite VP and Global Head of Sustainability Marina Dirks told Trellis.

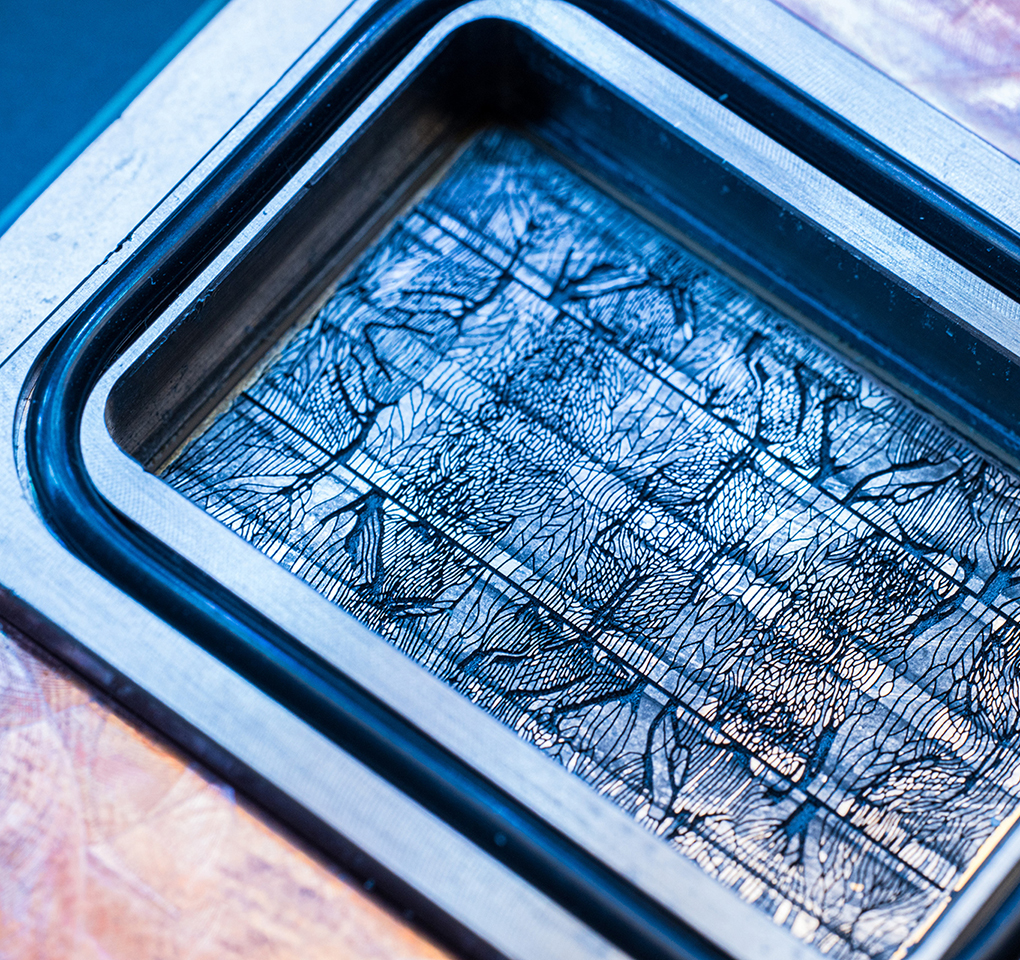

Last year, 40 percent of the company’s net sales included products with recycled content, up from 23 percent the previous year. In September, Samsonite launched what it considers a milestone: mainstream products that incorporate learnings from pilot projects. Components of the Paralux rolling suitcases include 100-percent recycled aluminum pull tubes; half of the hard polypropylene shells from recycled sources; and fully recycled fabrics, zipper tape and inner linings.

“Circularity in durable consumer products is an exciting and fast-developing space,” said Steve Diacono, strategic design manager at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation in England. “Many durable products have become almost synonymous with the curbside. We’ve all seen that old suitcase or dirty mattress abandoned on the street. These products still hold value, yet they often end up as waste because disposal is expensive or inconvenient for consumers, and recovery systems remain limited.”

Products with long lifespans are ideal for circular design, added Diacono, noting Samsonite’s experiments feeding material from old suitcases into new ones and formulating wheels for easy fixes should they fail.

Since 1910

Registered in Luxembourg with U.S. offices in Mansfield, Massachusetts, Samsonite saw $3.6 billion in 2024 sales for its Tumi, American Tourister and other brands, a modest 2.4 percent dip from 2023. The company has been listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange since 2011, following numerous twists since its 1910 origins as the Shwayder Trunk Manufacturing Company of Denver.

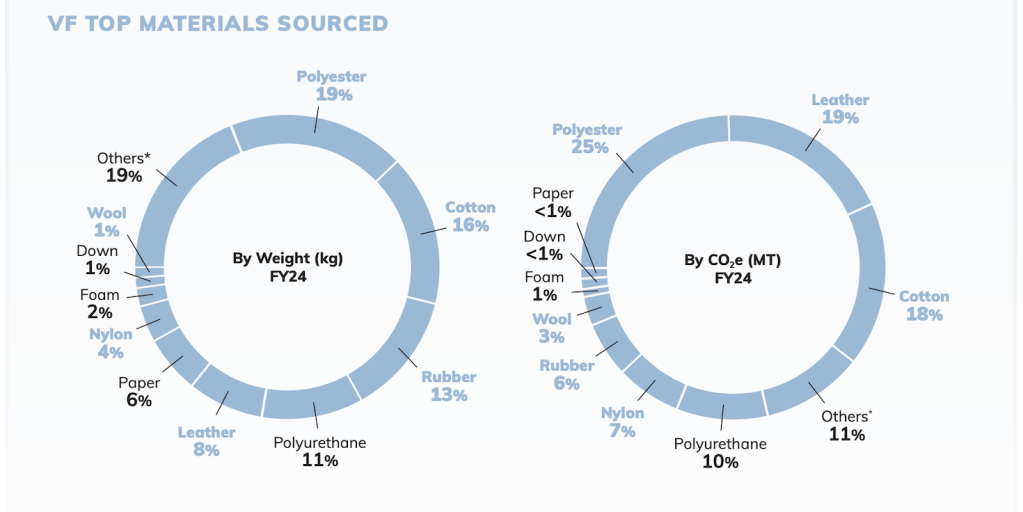

Recycled materials are core to Samsonite’s emissions goals, validated in March by the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi). Ninety-five percent of its climate footprint derives from Scope 3. Eighty percent comes from purchased goods and services, which Samsonite aims to slash 52 percent by 2030 over 2022 levels per unit of gross profit. (Its emissions progress is tied to financial performance.)

Consulting globally across sourcing, product development, designers, brand and marketing personnel, Dirks’ team found out about future product plans, then explored how to dial up their recycled content.

“Our vision is to really use our leadership position to create a more sustainable future for our industry,” she said. Conducting a materiality assessment including third-party suppliers confirmed that approach.

Sourcing varies geographically. Initially, for manufacturing in Belgium, the company sourced recycled polypropylene from things like yogurt cups and other household waste. In Asia, it took plastic from recycled laundry machine barrels.

Circular evolution

The emphasis on circular materials emerged in 2018 with Samsonite’s first “eco collection,” which used recycled plastic bottles in linings and soft casings.

Smaller collections, like the Essens Circular suitcases introduced this spring, were partly sourced from material in suitcases returned by consumers. They incorporate plastics derived from restaurant cooking oil. Supplier LyondellBasell provided the “biocircular” material, certified under the International Sustainability and Carbon Certification mass balance approach.

Essens also marked Samsonite’s first use of Digital Product Passports, letting consumers scan a QR code to view lifecycle details.

Testing and tradeoffs

Samsonite tests its products in regional labs. Most suppliers test components, too. The company evaluates each component before assembly: Can it handle high heat and humidity? How about rough handling?

Sustainable design must balance durability, repair and innovative materials, according to Dirks, former director of global sustainability at Tiffany & Co.

Plastics recycled multiple times can become less durable, unlike aluminum. That’s why outer shells, fabric linings and pull handles have higher recycled content than wheels, which are central to suitcase functionality.

“We all know how a piece of luggage might be thrown around by an airline no matter how careful they are,” Dirks said. “It just needs to be able to withstand a lot more than some other applications of recycled materials.”

Repair

Dirks’ team also considers the tension between long-lasting products and eventual repairs. “If you buy a car, it’s to be expected you service it once a year,” she said. Samsonite consumers already “have that expectation that no matter how durable it is, things happen.”

For those cases, Samsonite seeks to simplify repair options through stores, at home and via third-party centers. Paralux owners can replace a busted wheel or pull handle at home, guided by videos using shipped parts. “The only thing you need to replace is a pin,” Dirks said. Shipping small parts rather than whole products further reduces emissions.

Diacono noted that steps like these are the kind of progress needed for durable consumer goods. “To unlock real impact, circular business models — such as rental, repair and refurbishment — need to scale,” he said.

Other sustainability progress

Samsonite continues to use 100 percent renewable energy in its own operations, achieved two years ahead of schedule in 2023. It also surpassed a 15 percent carbon intensity reduction goal for 2025. However, the company has not submitted a net zero goal to the SBTi. Dirks, who reports to CEO Kyle Francis Gendreau, said the company is watching how the SBTI’s standards evolve. However, current sustainability metrics don’t incentivize product durability and other circular practices.

“From a target-setting perspective,” Dirks said, “that puts you in a worse place than if you were to design a product that just has a very low carbon footprint, but maybe breaks a year into use.”

The post Samsonite wheels its way to circular luggage appeared first on Trellis.